Matt Skoglund of North Bridger Bison holds feathers he found on the grounds of his ranch. “Our family loves birds, and that goes hand in hand with our passion for conservation ranching,” Skoglund says.

It doesn’t take much to notice the dramatic landscape surrounding Bozeman. Golden green expanses rise up to meet peaks that ripple the landscape. For mountain-town folks, it’s the high country where most of the attention is fixed. Dramatic and mysterious, mountains allow for adventurous thrills. But far below them and supporting their grandeur is a sneaky star. Overlooked both in its beauty and its importance are the grasslands.

“Grasslands are super expansive ecosystems that occur all across the globe and support high levels of biodiversity,” says Montana State University ecology professor Andrew Felton.

Felton studies grasslands by examining plants. According to him, grasslands cover about 30 percent of the world’s land mass, “and the Northern Great Plains are one of the largest intact grassland regions on Earth, which is pretty amazing to have right in our backyard.”

Especially amazing is grasslands’ ability to support wildlife and sequester carbon. According to the World Wildlife Fund, the Northern Great Plains alone support 2,900 plant species, 200 bird species, 120 mammal species, and tens of thousands of insect species.

“The common value is the care for the entire ecosystem. It’s not just us and our cows; it’s care for us, our cows, the birds, the soil, the predators—it’s everything.” —Meagan Lannan, Barney Creek Livestock

Prairie ecosystems also help remove carbon from the air, which is essential for slowing the pace at which our world will experience the impact of climate change. “We’ve all heard of photosynthesis; that’s essentially plants taking CO2 from the air and turning it into sugar to help them grow, but it’s also a way for carbon dioxide to be taken in and stored in the soils,” Felton says.

Unfortunately, Bozeman’s backyard sneaky star is struggling. Five years ago, the National Audubon Society concluded in its North American Grasslands and Birds Report that the prairie ecosystem is severely fragmented. According to Audubon, only 11 percent of the tallgrass prairie, 24 percent of the mixed-grass prairie, and 54 percent of the shortgrass prairie that once covered much of the continent remain.

“Grasslands are the most imperiled ecosystem,” says Audubon Communications Manager Anthony Hauck.

Hauck, bright-eyed and passionate in his work, explains that grassland habitat is cut away by dwelling development and cultivated agricultural lands. As the amount of grassland shrinks, so does its ability to act as a carbon sink and support biodiversity.

To combat the loss of grassland, Audubon is promoting healthy livestock grazing practices through a bird-friendly certification program. And several ranches in Montana have already stepped up to the plate.

Audubon recognizes that ranching takes place in an ecosystem, and that ranching—if done in a specific way—can leave enough to maintain equilibrium for the other species in that ecosystem. And according to participating Paradise Valley rancher Meagan Lannan of Barney Creek Livestock, this certification highlights a holistic approach to raising food.

“The common value is the care for the entire ecosystem,” she says. “It’s not just us and our cows; it’s care for us, our cows, the birds, the soil, the predators—it’s everything.”

STATEMENT OF VALUES

Audubon’s green certification seal matches the green practices of ranchers. Similar to the little orange butterfly found on packaging to represent non-GMO project verified, the little green “Audubon Certified, Bird-Friendly Land” seal appears on participating ranches’ meat products to help consumers make informed decisions about their purchases.

“But it’s more than just a certification,” Hauck says. “Sure, it might add value to the product itself, but having the certification is more of a statement on the rancher’s values.”

Ranchers can earn the bird-friendly certification by using conservation ranching practices that protect the grasslands on which their cattle live. This includes rotational grazing and avoiding pesticides, herbicides, tilling, or plowing.

Without chemicals insects are allowed to flourish, and without tilling worms and other ground-dwellers are able to dig in, providing plenty of grub for birds. “The idea is to create a healthy habitat for different types of birds,” Hauck says. “Some species prefer shorter grasses; others prefer longer grasses—and rotating the cattle helps to create a mosaic of different grass lengths.”

Keeping cattle off a section of land can help the vegetation grow back strong and long to provide bird habitat and it also improves soil health. Nutrient-dense soil produces healthier vegetation that better nourishes livestock. “It’s grazing for good,” Hauck says. “If we manage lands for biodiversity, we could bring an ecosystem back to life.”

For some ranchers, this practice has become an ethos. Focusing on how to effectively graze their cattle to promote biodiversity in the ecosystem, healthier soils, and nutrient-dense food, these ranchers believe they can help better the land and the stomachs of the people who live on it.

‘LETTING THE LAND REST’

Over the Bridger Mountain range from Bozeman lie acres of open land. Long fence lines meet each other in a patchwork that divides the grassland into individual properties serving as farms, homes, and ranches. And one of these ranches, in particular, has a mosaic of its own.

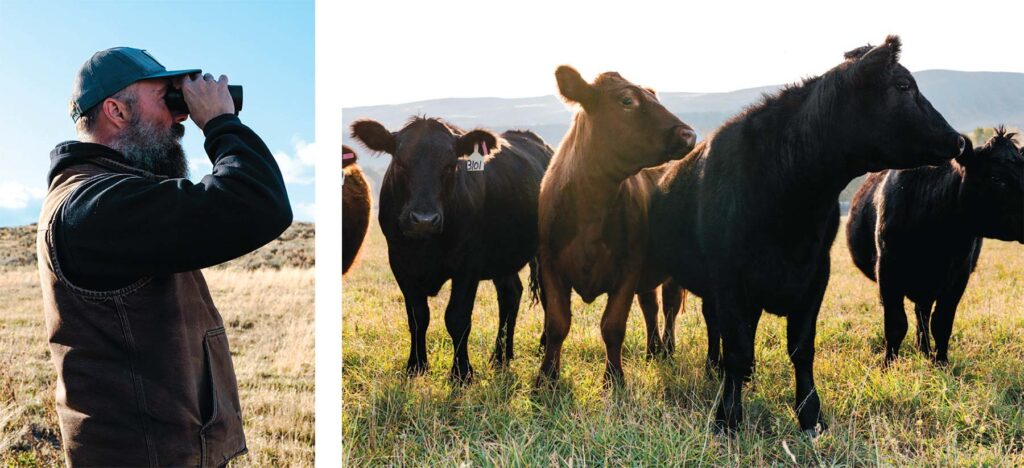

“We’re letting the land rest,” says Matt Skoglund, the owner of North Bridger Bison. Skoglund looks out the window of his ATV at the electric fences that partition sections of grassland in different stages of growth. Skoglund raises grass-fed bison and has had conservation ranching practices built into his business since the beginning.

“Our goal is to provide habitat for all types of wildlife and maximize the amount of biodiversity here,” he says. “Birds are a part of that.”

To accomplish this task, Skoglund “rests” the land, meaning he rotates his grazers, giving portions of the ranch time to regrow. This lets the soil rejuvenate and grow taller grasses.

“I keep rotating [the bison] so that they can graze in a new area, and then we have a whole ecosystem with different lengths of grasses,” he explains, adding that the more biodiversity found on a landscape, the more resilient and healthier are the animals that belong to that ecosystem.

“It makes us feel great that we have this certification,” he says. “We have a deep love of birds, of the land, and for conservation, and this is a seal to showcase that.”

‘FEELS LIKE A PARTNERSHIP’

The Yellowstone River, unfurling like a ribbon torn from the present of the Absaroka Mountain Range, lies just a mile from Barney Creek Livestock in Paradise Valley. Songbirds keep the air alive with sound as the Lannan family loads up their truck.

Heading out to manage a pasture that isn’t their own, Pete, Meagan, and Maloi Lannan talk about the game plan: who’ll move the cows, wind up one section of the fence, and unwind another. Like North Bridger Bison, the family earned their bird-friendly certification on their ranch, and now they’re taking their practices to other land in the valley.

“You know, when we first moved onto our land, we asked, ‘How can we use cows to bring back land?’ and here we are,” Meagan says.

This wasn’t done with certification in mind. In fact, Pete wasn’t interested in certifications at all. In order to showcase a certification on a food product, it usually takes time, energy, and money that farmers and ranchers don’t have. “I think either you’re doing it, or you’re not. So whenever Meagan would come to me with an idea for a certification, I’d say ‘no’,” Pete says. “But with Audubon, it fit into what we were already doing. They share similar values with us.”

The Lannans were already using regenerative ranching practices to increase bird habitat and enrich their soil, so going through the process with the Montana chapter of the Audubon Society seemed like the perfect fit.

“It feels like a partnership,” Meagan says. “They’re into teaching us just as much as we’re into teaching them.” The Montana chapter travels out to Barney Creek Livestock to check up on their methods and also conducts surveys. Sometimes they sit out on the ranch for hours, counting the number of birds they find by sound. “They’re passionate, you know? And now I get so excited when I think I find evidence of a new species,” Meagan adds.

‘WHAT WE’RE NOT DOING’

Teeming with wildlife, P Bar Ranch sits nestled in the foothills of the Beartooth Mountain Range, just south of Big Timber. Shy peaks peep over the bluffs to look in on the operation, where husband and wife Austin and Jaimie Stoltzfus are getting ready to move their cattle.

Slinging saddles and tightening tack, Jaimie and Austin prefer to move the herd from atop their horses. “We want to give to the land instead of extracting from the land,” says Jaimie. “Healthy soil, healthy ecosystem, and healthy grasses, that’s something we can help with, and that’s where the bird-friendly certification comes in.”

To the Stoltzfus family, the Audubon certification and partnership are a great way to stay accountable. “The National Audubon Society conservation ranching program is really strategic to make sure we’re supporting our mission in the best way we can,” Jaimie explains.

In addition to rotational grazing and staying away from pesticides and plows, the Stoltzfus family grazes multiple species together in the summer, they plant cover crops, and they test their soil. Over time, these tests will reveal whether their management practices are helping with nutrient density.

“We’re trying to create really good soil, which has a ripple effect on everything else,” Jaimie says. “So much of it is what we’re not doing. Letting the land be is sometimes the best practice.”